Apistogramma elizabethae, or Elizabeth’s Dwarf Cichlid, is a colorful dwarf cichlid that originates from the blackwater habitats of South America. The scientific name was given in honor of Elizabeth Cabot Cary Agassiz (1822-1907), the second wife of J. L. R. Agassiz, who participated in the Thayer Expedition (1865-1866) and was the principal author of a book about the journey.

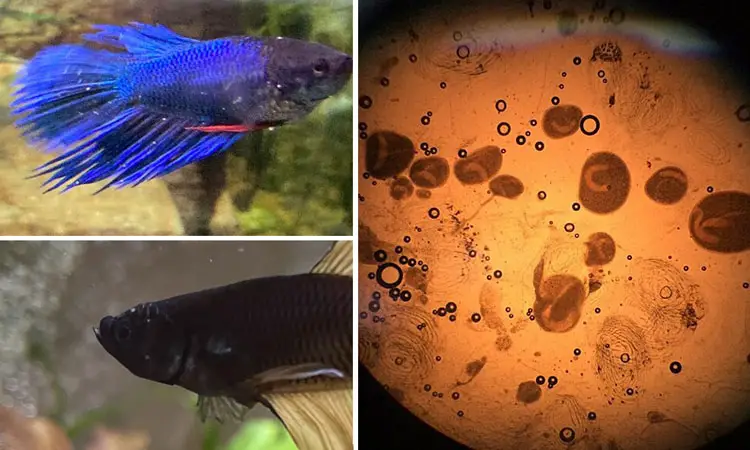

There are two main color variations of A. elizabethae available in the trade, including red and blue, depending on the locality from which they were collected.

There are two main color variations of A. elizabethae available in the trade, including red and blue, depending on the locality from which they were collected. These fish display sexual dimorphism, meaning that there are distinct physical differences between males and females.

This medium-sized Apistogramma fish also exhibits more aggressive behavior than other Apistos during spawning seasons.

Their need for very specific water conditions makes them a perfect addition to a Rio Negro biotope aquarium; however, it also makes them challenging to breed.

Before you make the purchase, let’s talk about the characteristics of this amazing fish, how to care for them, and their reproduction requirements.

What is the Native Habitat of Apistogramma elizabethae?

A. elizabethae is native to two main tributaries of the Rio Negro, including the Uaupés River and the Içana River. The Rio Negro is the largest blackwater river in the world, located in northwestern Brazil and eastern Colombia.

The river waters are stained by tannins from decaying organic matter, giving them an almost black tint. This type of environment is also characterized by extremely soft and acidic water, high levels of humic acids, and a low concentration of essential minerals.

These are the most important water parameters of the native habitat of A. elizabethae.

- Temperature: 72 to 84° F (22 to 29°C)

- pH: 4.5 to 6.0

- General Hardness (GH): < 1 dGH

- Conductivity: < 10 µS/cm

They often inhabit areas near the river banks where the water is shallow and surrounded by dense forests. The riverbed substrate is composed of fine white sand, a leaf litter layer, fallen branches, and plenty of aquatic vegetation.

Depending on the river where the A. elizabethae was originally collected, their prominent body color will be either red or blue.

What Are the Color Variations of Apistogramma elizabethae?

The most common color forms of Apistogramma elizabethae are as follows.

- Apistogramma elizabethae ‘Red’

- Apistogramma elizabethae ‘Blue’

Apistogramma elizabethae ‘Red’

A. elizabethae ‘Red’ refers to the wild-caught specimens from the Içana River. Males typically have a shiny, metallic blue body with a bright red belly and head.

Several captive-bred color morphs of this wild form exist. The most common color varieties include A. elizabethae ‘Red Belly’ and A. elizabethae ‘Super Red,’ which may have been color-enhanced with certain foods for more intense red.

Apistogramma elizabethae ‘Blue’

Apistogramma elizabethae ‘Blue,’ also known as A. elizabethae ‘São Gabriel da Cachoeira,’ is a naturally occurring color form of Apistogramma elizabethae that originates from the town of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, near the Uaupés River. It is rarer than the ‘Red’ counterpart.

In males, the base color of the body is usually silvery blue, accented by bright blue markings on their dorsal fins and yellow bellies. During the spawning season, both males and females exhibit a more intense yellow coloration.

In males, the base color of the body is usually silvery blue, accented by bright blue markings on their dorsal fins and yellow bellies. During the spawning season, both males and females show a more intense yellow coloration.

However, this variety has not been commercially bred because it is less vibrant than its cousin, the most popular Apistogramma agassizii ‘Blue’.

How to Tell a Male From a Female Apistogramma elizabethae?

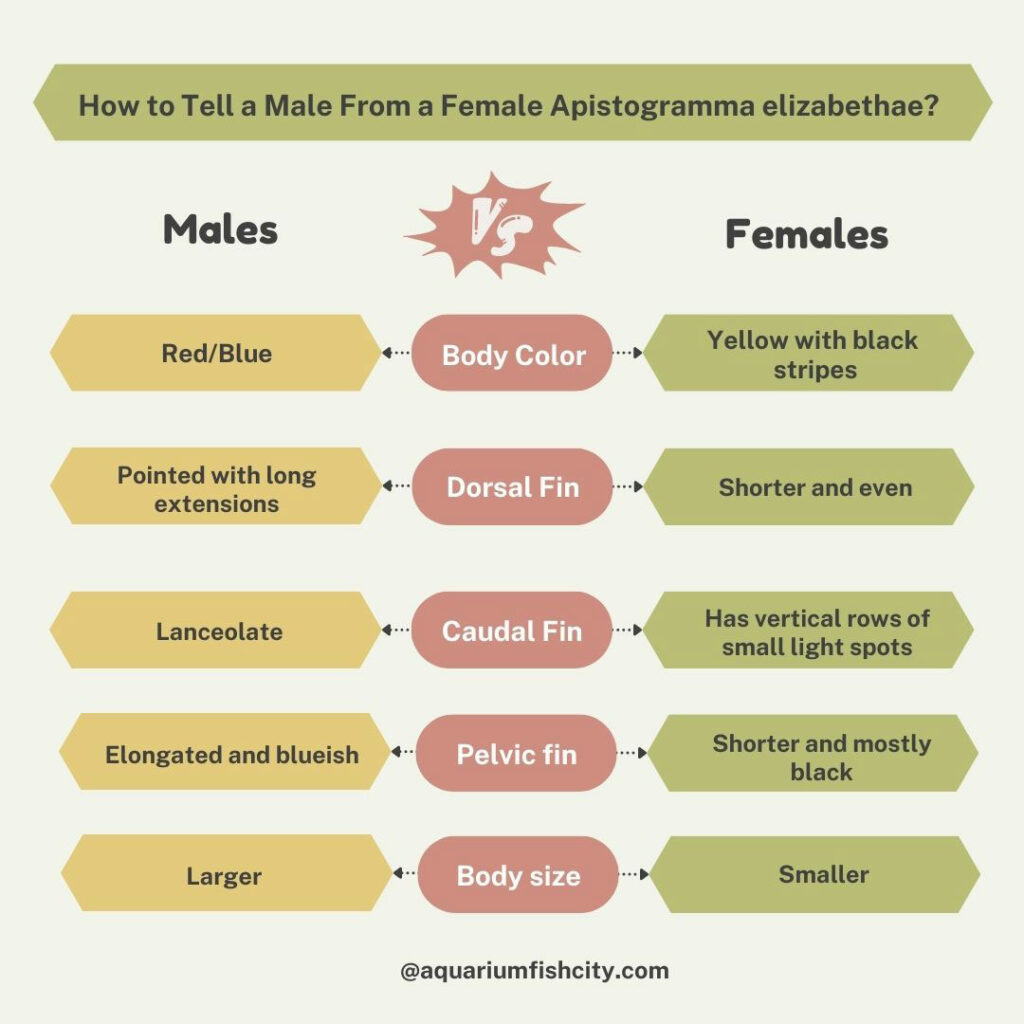

Here are some of the characteristics to tell a male from a female Apistogramma elizabethae.

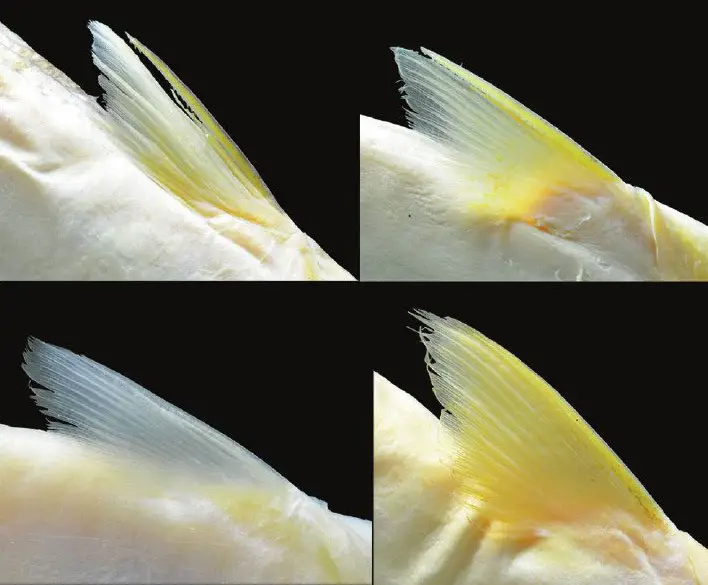

- Dorsal fin: The male’s dorsal fin is longer and more pointed than the female’s, and it contains 5-6 spines. The female’s dorsal fin is shorter and even.

- Pelvic fin: The male’s pelvic fin is elongated and blueish, while the female’s pelvic fin is shorter and mostly black.

- Caudal (tail) fin: Males develop a lanceolate caudal fin. In females, the caudal fin has vertical rows of small light spots that give the appearance of striping.

- Coloration: Males are more colorful than females. During courtship and breeding, females will exhibit a yellowish-orange coloration covering the anterior part of their bodies, making their black lateral spots and facial stripes perfectly straight.

- Size: Males are considerably larger than females.

Keep in mind that juvenile fish smaller than 1.5 inches (4 cm) are too small to tell the differences.

How Big do Apistogramma elizabethae Get?

Apistogramma elizabethae males can grow to be around 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) in total length, while females tend to be slightly smaller, reaching approximately 1.6 inches (4 cm) in total length.

Are Apistogramma elizabethae Aggressive?

Yes, Apistogramma elizabethae are slightly more aggressive than many other beginner-friendly Apistos due to the males’ harem polygyny mating system. In this system, each male mates with more than two females. A male can be very aggressive towards females who are not ready to spawn.

In the home aquarium, it is generally impractical to recreate this system due to the limited space. As a result, female-female intrasexual aggression occurs quite often, leading to stress and potential injury.

The females are also extremely protective of their brood, sometimes even attacking the male if he gets too close to the fry.

To ensure the well-being and longevity of Apistogramma elizabethae, it is best to get either just a trio of one male with two females or a large group consisting of at least three males and 4-6 females.

How Long Do Apistogramma elizabethae Live?

The average lifespan of Apistogramma elizabethae is around two years in captivity, as stated by a 1991 statistical study of 7,532 tank-raised specimens from 23 different Apistogramma species by Dr. Sven O. Kullander. However, it has been reported that they can live up to 5 years under ideal conditions among aquarium hobbyists.

Small fishes tend to have a shorter lifespan than large ones, and many factors play into how long you can expect your fish to live, including their genetics, diet, water quality, and stress levels.

As with any freshwater aquarium fish, providing good care by creating optimal environments is the key to a long and healthy life for your Apistogramma elizabethae.

How to Take Care of Apistogramma elizabethae in Home Aquariums?

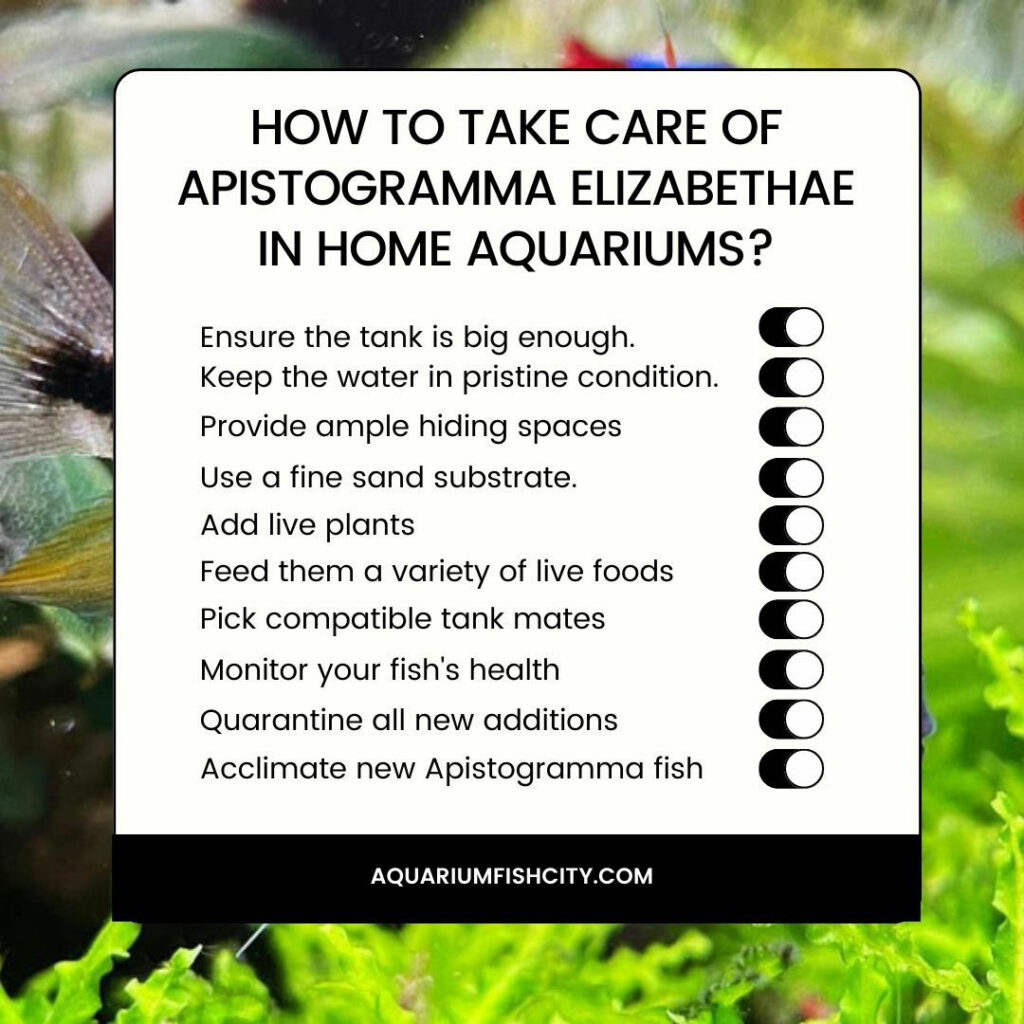

Here are 10 key tips on how to take care of Apistogramma elizabethae in aquariums.

- Ensure the tank is big enough. A 20-gallon Long (75 liters) tank is the minimum size for a trio of Apistogramma elizabethae. For large groups, you’ll want to ensure that each female has a brooding territory of at least 12 inches (30 cm).

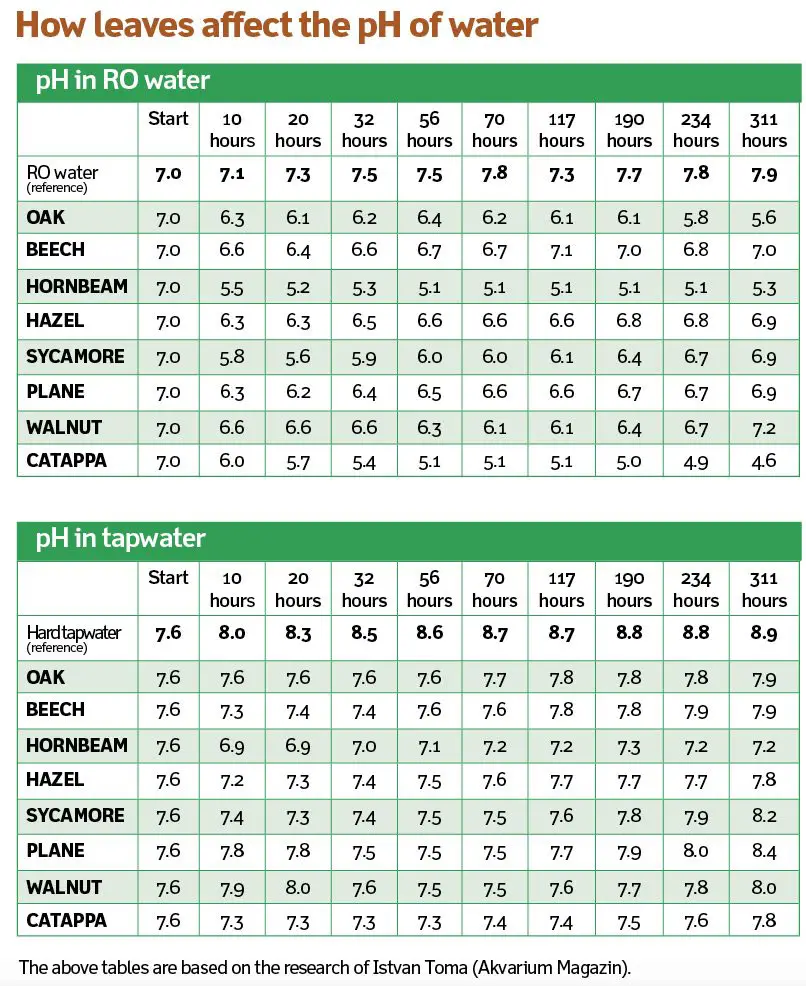

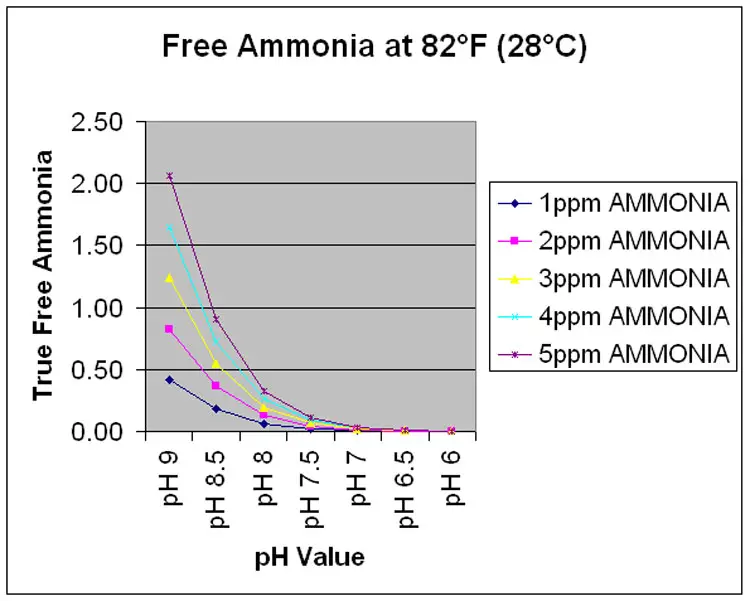

- Keep the water in pristine condition. The ideal water chemistry parameters for A. elizabethae include a pH of 4.5 – 6.0, general hardness between 1-3 dGH, conductivity less than 10 µS/cm, and a temperature of 72 – 84°F (22 – 29°C). Perform regular water changes of around 10-15 percent weekly. Conductivity and ph levels must be carefully adhered to for keeping this blackwater species in an aquarium. The very soft, acidic, and low conductivity environments can be created by using a RODI (reverse osmosis de-ionized) water system with peat moss and catappa leaves.

- Provide ample hiding spaces and visual barriers. Like most other types of Apistogramma, A. elizabethae are cave spawners and like to establish their own territory, so provide them with lots of caves and hardscapes as sheltered areas. Overturned flowerpots and half coconut shells are great options for creating suitable caves.

- Use a fine sand substrate. A fine-grained sand (0.5-1.7 mm grain size) substrate serves two main purposes: it’s safe for these sand-sifting fish to dig in, and it helps replicate their natural environment.

- Add live plants. Some floating plants are preferred. Not only do they subdue the lighting, but they also offer aesthetic and biochemical benefits. These floating plants are the best choices for Apisto tanks: Anacharis, Amazon Frogbit, Butterfly Fern, Dwarf Water Lettuce, and Hornwort.

- Feed them a variety of live foods. To bring out their classic red and blue coloration and boost their health, offer live foods such as bloodworms, daphnia, baby brine shrimp, and black and white mosquito larvae.

- Pick compatible tank mates. Ideal tankmates for Apistogramma elizabethae include pencilfish, hatchetfish, South American tetra species, and diminutive catfish like Corydoras catfish and Otocinclus catfish. Some potentially good tankmates may include freshwater angelfish, keyhole cichlid, and Geophagus cichlid.

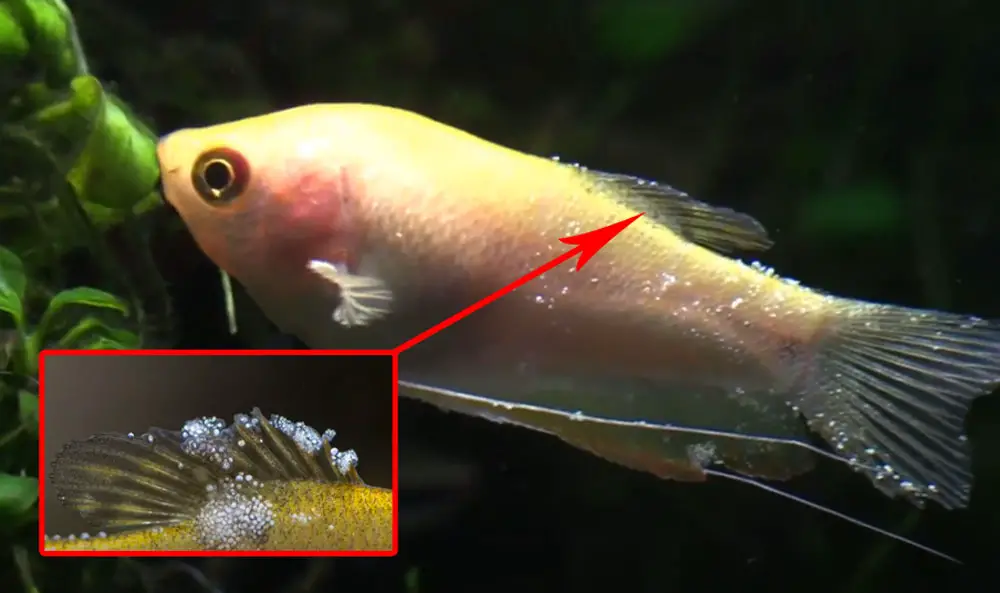

- Monitor your fish’s health. Watch your fish for lethargy, loss of appetite, swimming difficulty, loss of color, scratching against decorations, white spots, cloudy eyes, white body film, and any other signs of illness. If you notice any of these symptoms, take action immediately.

- Quarantine all new additions. Quarantining is a critical step in preventing the spread of parasites and bacterial infections. Make sure to quarantine all new additions for at least 2-3 weeks in a quarantine tank(QT) before introducing them into the tank.

- Acclimate new Apistogramma fish. You will also need to acclimate your Apistogramma elizabethae either by the drip or float method. Never add a fish directly to the tank water as it will lead to shock and stress.

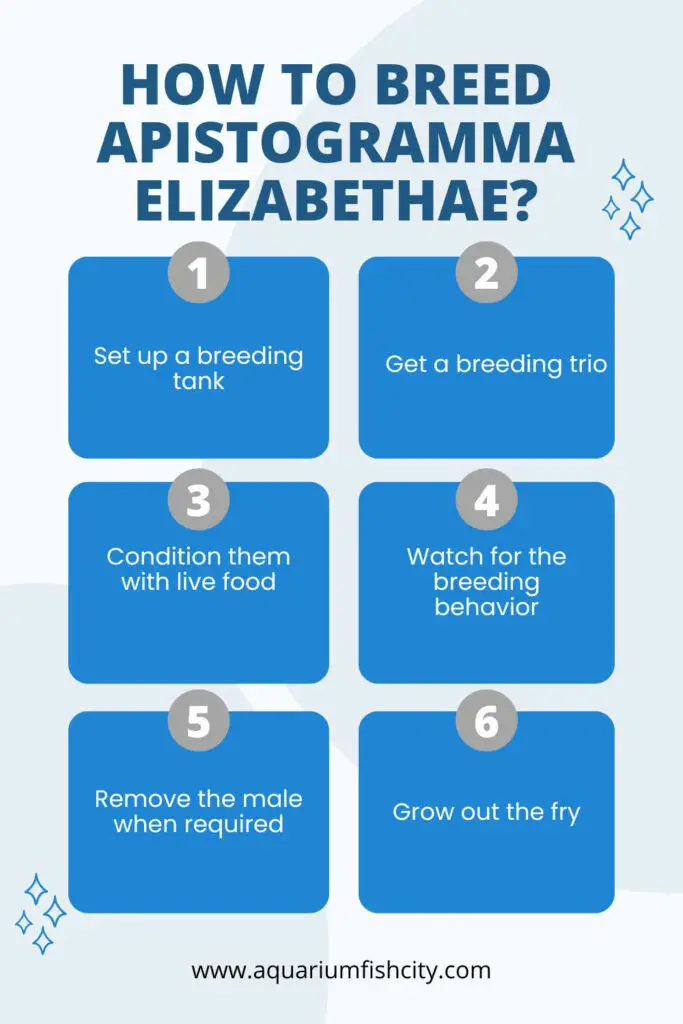

How to Breed Apistogramma elizabethae in a Tank?

Here are the step-by-step guidelines to successfully breed Apistogramma elizabethae in a tank.

Step 1: Set up a breeding tank.

Use a 20-gallon long tank as a separate spawning tank with a pH of 5 – 6, general hardness (GH) between 1-3 dGH, and conductivity less than 100 µS/cm (or TDS < 50 ppm), and water temperature range of 75 – 79°F (24 – 26°C).

It’s worth noting pH levels and water temperature influence the sex ratio of fry. Lower temperatures (< 76°F) and higher pH levels (> 5.5) seemed to produce more females, whereas higher temperatures and lower pH levels yielded a higher ratio of males.

The tank should have a fine-grained sand substrate with catappa leaves. Add some floating plants and consider covering the sides of the tank with aquarium backgrounds to reduce light, make them feel more secure, and assist in egg fertilization. A group of pencilfish also sends a strong message to the Apistos that this place is safe for reproduction. These fish are cave spawners, so provide each fish with one or two caves.

Step 2: Get a breeding trio.

The best way to obtain a breeding trio is to purchase a group of at least six juveniles and raise them to maturity together. They will reach sexual maturity around 6 – 9 months of age. When choosing the breeding fish from your own group, look for bright-colored males with the healthiest and most active females.

Alternatively, you can buy a breeding trio of Apistogramma elizabethae online.

Step 3: Condition them with live food.

After introducing the breeding trio to the tank, feed them live food and monitor them closely to ensure they are getting along well.

Step 4: Watch for the breeding behavior.

In Apistogramma dwarf cichlids, the female starts a courtship ritual to attract the male near her cave. The male will perform tail-beating if he is interested in the female. The courting process may last for several days in new pairs and 2-3 hours in established pairs.

The spawning takes place secretly in the cave, with up to 30 eggs per spawn being deposited on the ceiling of the cave. In 1 to 3 days, the fry will hatch at 77°F (25°C), and they become free-swimming after three days.

Step 5: Remove the male when required.

The brooding female will viciously protect the fry and might become overly aggressive toward the male. If this happens, it’s best to remove the male.

Step 6: Grow out the fry.

Fry must be fed very small foods, such as infusoria, rotifers, and newly hatched brine shrimp. During this time, ensure the tanks are well aerated and the water is kept very clean. Feed the fry multiple times per day and perform daily water changes.